The conference room in the Omaha hotel was all soft lighting and expensive carpet, but to George, it might as well have been a prison block. He was two days into a three-day financial summit, a gathering of guys his age—mid-sixties, mostly—all talking about managed portfolios and market volatility. It was the kind of thing that had once energized him, but now, at 67, it just felt like a chore. He missed his wife, Helen. He missed his own armchair. He missed the quiet comfort of their home in Lincoln.

His phone, face-down on the polished mahogany table, vibrated with a soft hum. He ignored it. The speaker droned on about interest rate forecasts. A minute later, it vibrated again. And again. Someone was insistent.

Slightly irritated, he tilted the phone just enough to see the screen. A string of messages from his next-door neighbor and oldest friend, Carl.

“George, you there?”

“Give me a call when you get this.”

“It’s about Helen.”

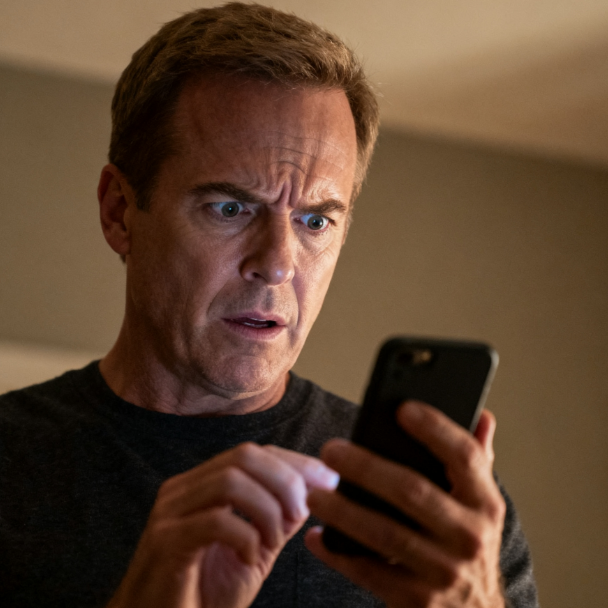

The words “It’s about Helen” sent a jolt of pure ice through his veins. His heart, which had been beating a slow, bored rhythm, suddenly kicked into a frantic gallop. Visions of ambulances, falls, a sudden illness—all the fears that live in the quiet corners of a long marriage—flooded his mind. The conference room, the speaker, the charts—it all melted into a meaningless blur.

He muttered an apology to the man next to him, stood up so quickly his chair scraped loudly against the floor, and practically ran into the hallway, his phone clutched in his sweaty hand. He didn’t call. Carl had sent one more message. A video.

His thumb trembled as he tapped to open it. The video was shaky, shot from Carl’s kitchen window, which had a perfect view of George’s backyard. The timestamp showed it was from about twenty minutes ago.

The video showed Helen. She was wearing her old gardening jeans and a worn-out Nebraska Cornhuskers sweatshirt, her gray hair pulled back in a messy ponytail. She wasn’t sick. She wasn’t hurt. She was… dancing.

But this was no ordinary dance.

She was holding a wooden spoon like a microphone, her eyes closed, swaying with a kind of abandoned, joyful rhythm George hadn’t seen in years. The audio was faint, picked up from a distance, but he could just make it out. It was “Brown Eyed Girl.” Their song. The song that had played at their wedding reception in 1978.

She was singing along, belting out the lyrics to the empty backyard, the spoon-microphone held close to her lips. Then, she did a slow, slightly silly twist, pointing the spoon toward the bird feeder as if inviting the chickadees to join in. A laugh burst from her, clear and bright, carried faintly on the phone’s microphone. It was a laugh of pure, unadulterated joy. A laugh he realized he hadn’t truly heard in a long, long time.

The video ended.

George stood frozen in the plush hallway, the silence ringing in his ears. The initial wave of relief that she was safe was immediately washed away by a second, more powerful wave of… shame.

He saw it all with devastating clarity. The video wasn’t just a recording of his wife dancing. It was a mirror held up to their life, and he didn’t like what he saw reflected.

He saw the woman he had fallen in love with—the vibrant, funny, spontaneous girl who’d drag him onto a dance floor anywhere, anytime. And then he saw the last few years. His quiet retirement. His focus on the news, on his routines, on the quiet, predictable comfort of their life. He’d started treating their home like a library, a place for hushed tones and quiet contemplation. He’d mistaken contentment for complacency.

He had, without ever meaning to, become a man who put his wife on mute.

And here she was, when she thought no one was watching, bursting with a music that he had somehow stopped hearing. She wasn’t just dancing in the backyard. She was dancing because she was free. Free from his quiet presence, his predictable routines, his unspoken expectation of calm. She was celebrating her own spirit, a spirit that was clearly still very much alive, a spirit he had been neglecting.

Carl called then. George answered, his throat tight.

“You see it?” Carl asked, chuckling. “Sorry, man, I didn’t mean to scare you. I just saw her out there and it was so darn funny I had to film it. She’s a hoot! Didn’t know she had those moves!”

“Yeah,” George managed to croak out. “She does.”

He ended the call quickly. He didn’t need to explain. He walked back into the conference room, but he didn’t sit down. He gathered his notebook and pen.

“Leaving early, George?” the man next to him asked.

“Emergency,” George said, and it was the absolute truth.

He was in his car, heading south on I-80 within fifteen minutes. The three-hour drive felt both endless and instantaneous. He didn’t listen to the news radio. He played “Brown Eyed Girl” on a loop, and with each play, he saw her in that backyard, laughing, dancing, so fully and completely herself.

He wasn’t rushing home out of worry. He was rushing home out of love. And out of fear—the fear of having almost lost something precious without even knowing it was gone.

He pulled into the driveway just as the sun was beginning to set. He could see Helen through the kitchen window, stirring something on the stove. The picture of domestic normalcy.

He walked in through the back door, his suitcase still in the car. She turned, her face a mask of surprise.

“George! What on earth? Is everything alright? Did the conference end early?”

He didn’t answer. He walked straight to the old Bluetooth speaker on the counter, fumbled with his phone for a second, and found the song.

As the first chords of “Brown Eyed Girl” filled their quiet kitchen, her eyes widened in confusion, then recognition. A faint blush crept up her cheeks. She knew. She’d been caught.

“George, I… I was just being silly,” she started, waving a hand dismissively.

He walked over to her, took the wooden spoon from her hand, and placed it on the counter. Then he took her hand, her familiar hand, dotted with age spots and etched with the history of their life together.

“No, Helen,” he said, his voice thick with emotion. “You were being you.”

And there, in the middle of their kitchen, with the smell of simmering stew in the air, George, the quiet, predictable man, did something he hadn’t done in twenty years. He pulled his wife close and he danced with her. He was a terrible dancer, always had been. His steps were awkward and out of time.

But he was dancing. And Helen, after a moment of stunned silence, threw her head back and laughed—that same, glorious, backyard laugh—and let him lead her in a clumsy, shuffling circle.

He’d received a video that showed him a stranger. And he’d rushed home to reintroduce himself to his wife. The emergency wasn’t at home. It had been in Omaha, in a conference room where he’d forgotten the most important thing. The video had been a rescue mission. And he had arrived just in time.